We’ve been wondering that too! Check out this new paper from Caleb Weinreb and friends in Neuron on a new version of MoSeq called (what else?) shMoSeq, which gives you access to the behavioral states that organize mouse behavior on timescales of seconds to minutes.

OK, so what is shMoSeq, why did we build it, and what does it give us? shMoSeq is designed to address an important limitation of MoSeq, the unsupervised machine learning platform we’ve been developing to characterize behavior. MoSeq is powerful but frustrating. On the one hand, it converts video data into information about the structure of behavior; it identifies the set of syllables (sub-second, stereotyped action motifs like rears or turns) out of which mouse behavior is organized, as well as the sequence with which they occur in any experiment. This has yielded important information about how the brain structures the microarchitecture of behavior on a moment to moment basis (see here and here). But in the end, MoSeq basically gives you a statistical description of behavioral dynamics – it tells you nothing about *why* a mouse is doing what it is doing. It also doesn’t comport with our intuition that mice often organize their behavior over timescales of seconds-to-minutes, which is the timescale at which humans typically describe behavior (and develop “ground truth” labels for supervised behavioral classifiers). Consistent with this, if we do some math (see the paper) it is clear that there are longer timescales that are organizing mouse behavior, even in a 30 minute open field experiment.

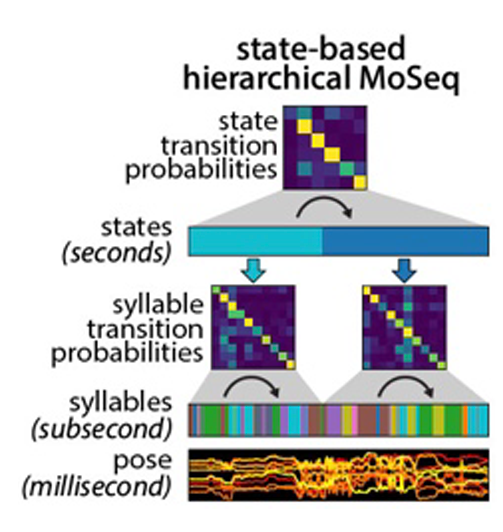

Caleb decided to tackle the longer timescale challenge by building a new, hierarchical version of MoSeq that has another layer on top of the layers corresponding to syllables (i.e., pose dynamics) and poses. This new top layer encodes behavioral states; mathematically, each state is a unique transition matrix, which describes the particular order in which syllables unfold over time. This definition means that all syllables can be used in all states — what differs is how they are sequences into coherent patterns of behavior. Applying shMoSeq to open field behavior yields a small number of higher order states that last seconds to minutes, and which occur in series over the entire experiment; applying shMoSeq to an open field with novel objects adds a couple of extra states, as does applying it to mice engaged in social interaction.

What are these states? Turns out, each corresponds to the mouse engaging with either some affordance in the arena (the walls, the floor, new objects, a social partner) in various ways, or with itself (by engaging in grooming and other care-related behaviors). In other words, it looks like during each one of these states the mouse is engaged in a self-directed task that reflects the specific affordances available in a given context. This gave Caleb the sense that maybe spontaneous behavior – as the title says – is a series of self-directed tasks. But how to prove this? Well we can’t directly (we are inferring something about the internal meaning of an external behavior after all), but Caleb generated evidence that this idea isn’t entirely unreasonable by asking the brain (in this case the pre-frontal cortex) what it seemed to care about….and it turns out during each of these states, the PFC encodes task-like variables reflecting those things that are most important for the animal to know to achieve a particular self-directed goal. For example, if a mouse is running along the arena wall, what matters most is where it is and how it is moving with respect for the wall, which turns out to be what is emphasized in the brain; if the mouse enters a different behavioral state, representations for those variables fade out and are replaced with representations for whatever variables matter in the new state.

There is all sorts of interesting and provocative stuff in this paper, but the key take-home is that with the right sorts of tools, we can now start to think about self-directed or spontaneous behavior as really being goal- or task-oriented; this aligns the study of natural behavior with long-established paradigms for studying how the brain solves problems after training. Congrats to Caleb and all the other authors!