The brain allows animals to successfully interact with a natural world that is rich with opportunity and rife with danger. These interactions are mediated by sensation and movement, which are used by animals to learn about their environment and to make useful predictions about the future. To address this question, the Datta lab embraces the perspective of the ethologists: if we are to understand how the brain works, we should ask of it questions that reflect the purpose for which it was designed. The lab therefore asks how the brain builds natural, self-directed behaviors — at timescales that range from minutes to a lifetime — and addresses how genes, sensory cues, affordances and social partners influence the structure and meaning of movement.

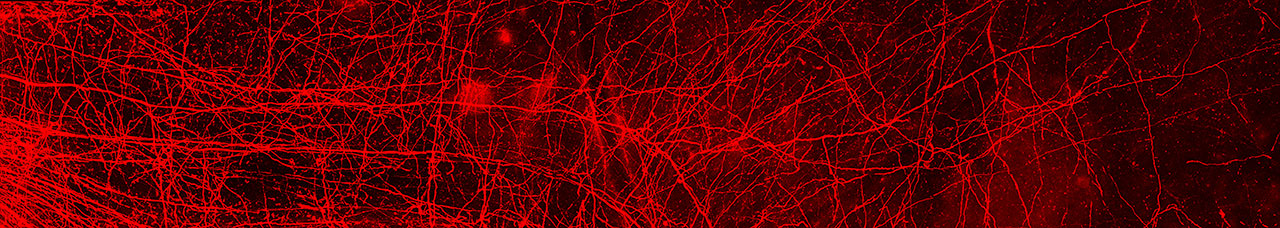

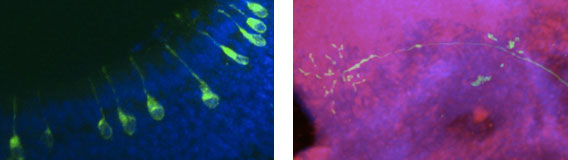

Furthermore, because so much of behavior is about collecting information, we pay particular attention to the olfactory system, the most important sense for a rodent, one essential for nearly every aspect of its survival in the real world. We ask how the mouse brain encodes information about smells at each neural station responsible for smell, from the peripheral sensors for odors to the deep recesses of the allocortex where smell information touches emotion, memory and cognition.

And we put action and sensation together by exploring neurobehavioral relationships in complex environments designed to dynamically challenge animals over long timescales. It is our hope that by exploring neural circuits in which sensation and ongoing action are necessarily intertwined — and by using ethology as a lever — we can gain purchase on the fundamental problem of how the brain enables animals to freely interact with the world.